Lulsegged Abebe PhD (lulseggedabebe@gmail.com)

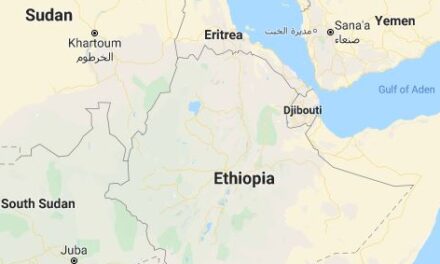

First, it accused Ethiopia of “intent to exercise hydro-hegemony” of the Nile waters, and now, despite ongoing negotiations, Egypt has written to the UN Security Council accusing Addis Ababa of failing to reach an agreement over the operation of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD).

Ever since Ethiopia announced plans to build a dam on the River Nile, Egyptian officials have fought tooth and nail to prevent its construction, even though Ethiopia was transparent and invited Egypt and Sudan to review the design and construction documents. There are reports that Cairo is so opposed to the construction of the GERD that in a meeting chaired by the late President Mursi, the Egyptians deliberated on how to sabotage the construction and even use military incursion. This is despite Ethiopia making it very clear that it considers the dam a platform for collaboration, a crucial aspect of its national development agenda, and a means to alleviate poverty.

Work on the dam begun in 2011. In April this year, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed declared that, despite the challenges posed by COVID-19, construction work on the dam remains on schedule, with the reservoir to be filled during the rainy season that starts in June. “Saving lives is our priority, while second to this we have the GERD,” Abiy told Ethiopians.

Whereas Ethiopia sees the GERD as a necessary piece of infrastructure in their country’s bid to become self-reliant with regard to energy needs (access to electricity in Egypt and Ethiopia is 100 and 45 percent respectively – so access in Ethiopia is less than half), Egypt has long considered the dam as likely to starve its population of water. This narrow assessment has also been exacerbated by Egypt’s perception of the Nile as a national security issue. Armed with two agreements, one signed in 1929 between Great Britain and Egypt, and another in 1959 with the Sudan, Egypt’s approach to matters concerning the utilisation of the Nile has tended to be aggressive and prescriptive. For years, Egypt has been able to rely on these frankly old and one-sided agreements reached between itself and the British, with no input whatsoever from Ethiopia, to determine how the Nile waters can be utilised. Egypt often fails to acknowledge the fact that Uganda has the Owen Falls Dam and Sudan has the Merowe Dam – both of which are built on the Nile, even though Egypt monitors the water levels and reports to Cairo, which is an intrusion of the national security of sovereign states.

There are of course various reasons for Egypt’s unease about the GERD. An oft-made argument against the dam by Egypt is that it will significantly reduce its country’s water supply, as mentioned above. With 90 percent of the country depending on the Nile waters, this is understandable. However, a careful look into the disagreement shows that something else might be behind the North African country’s incessant opposition to the GERD. From the very beginning of the building process, Ethiopia has given assurances that it will take all the necessary steps to ensure Egyptian and Sudanese interests are safeguarded. At every negotiation between Sudan, Egypt and Ethiopia, Ethiopian officials have dedicated a significant amount of time to giving cast-iron guarantees that such a promise will be kept. They have explained the need for the dam and have been keen throughout to address any suspicions harboured by the Egyptians.

When the ministers of foreign affairs from the three countries met in Washington DC on 13 January 2020, Ethiopian officials made it clear that the filling of the dam will provide appropriate mitigation measures for Egypt and Sudan. Ethiopia was also amenable to the suggestion that subsequent stages of filling should be carried out according to an agreed mechanism determined not only by the hydrological conditions of the Blue Nile and the level of the GERD that addresses the filling goals of Ethiopia.

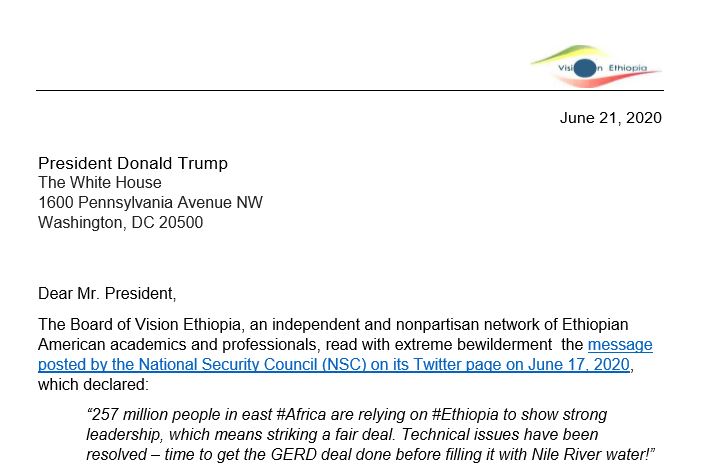

Why then did Ethiopia choose not to attend a subsequent meeting following the one on 13 January? According to the Ethiopian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ethiopia needed time to consult with stakeholders on a draft agreement the USA has prepared without the consent of the three countries. It is important to note that besides being brokered by the USA, the 13 January and subsequent meetings in DC were also attended by the US Secretary of the Treasury and the President of the World Bank as observers. It turns out the US stepped in after Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi reached out to President Donald Trump, a close ally, to help resolve the situation with Ethiopia. On its own, the US’s intervention in the dispute may not have been unprecedented, especially given America’s role as the policeman of the world, however, the fact that President Sisi, a party to the dispute (against the DOP article X), was the one who reached out to President Trump removed any semblance of impartiality in the negotiations.

It is now clear that President Trump would like to take credit for helping to resolve the dispute. But unless he is not fully informed of the developments so far, he surely must be aware that, as Gedu Andargachew, the Foreign Minister of Ethiopia has said recently, there are “outstanding issues that need negotiation”. As a sovereign nation, Ethiopia has every right to determine its economic agenda commensurate with its national interest, and no amount of foreign pressure will change this.

Egypt is free to take the issue to the UN Security Council, but as it will soon discover, these issues are best resolved through bilateral channels based on mutual agreements and understanding. If Egypt is interested in involving a third party, it would make sense to use the AU structures (AU Peace and Security Council) and the Nile basin countries, rather than reaching out to institutions which are outside Africa such as the Arab League, the USA, and now the UN Security Council. The 1929 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty and its modified version, the 1959 Agreement, may still be valid to Egyptian officials, however, none of these agreements considered the needs of other riparian countries – notably Ethiopia, which supplies 80 percent of the Nile waters.

We must not forget that Egypt rejected the Cooperative Framework Agreement signed by four Nile basin countries in 2010. That treaty sought to establish a framework to “promote integrated management, sustainable development, and harmonious utilisation of the water resources of the Basin, as well as their conservation and protection for the benefit of present and future generations”. It is therefore a bit rich for the same country to be accusing Ethiopia of failing to reach an agreement over the operation of the GERD.

The days of using threatening force are over. Ethiopia, as indeed all the other basin countries, have as much right to the Nile waters as Egypt. Ethiopia needs the Nile for its development just as Egypt needs it for its survival. Compromise will be key – but Egypt has to be fair.